How Demon Days Predicted The Future

On the seminal Gorillaz albums’ 20th anniversary, we explore how Damon Albarn’s genre-bending project predicted today’s everything everywhere music culture.

Intro

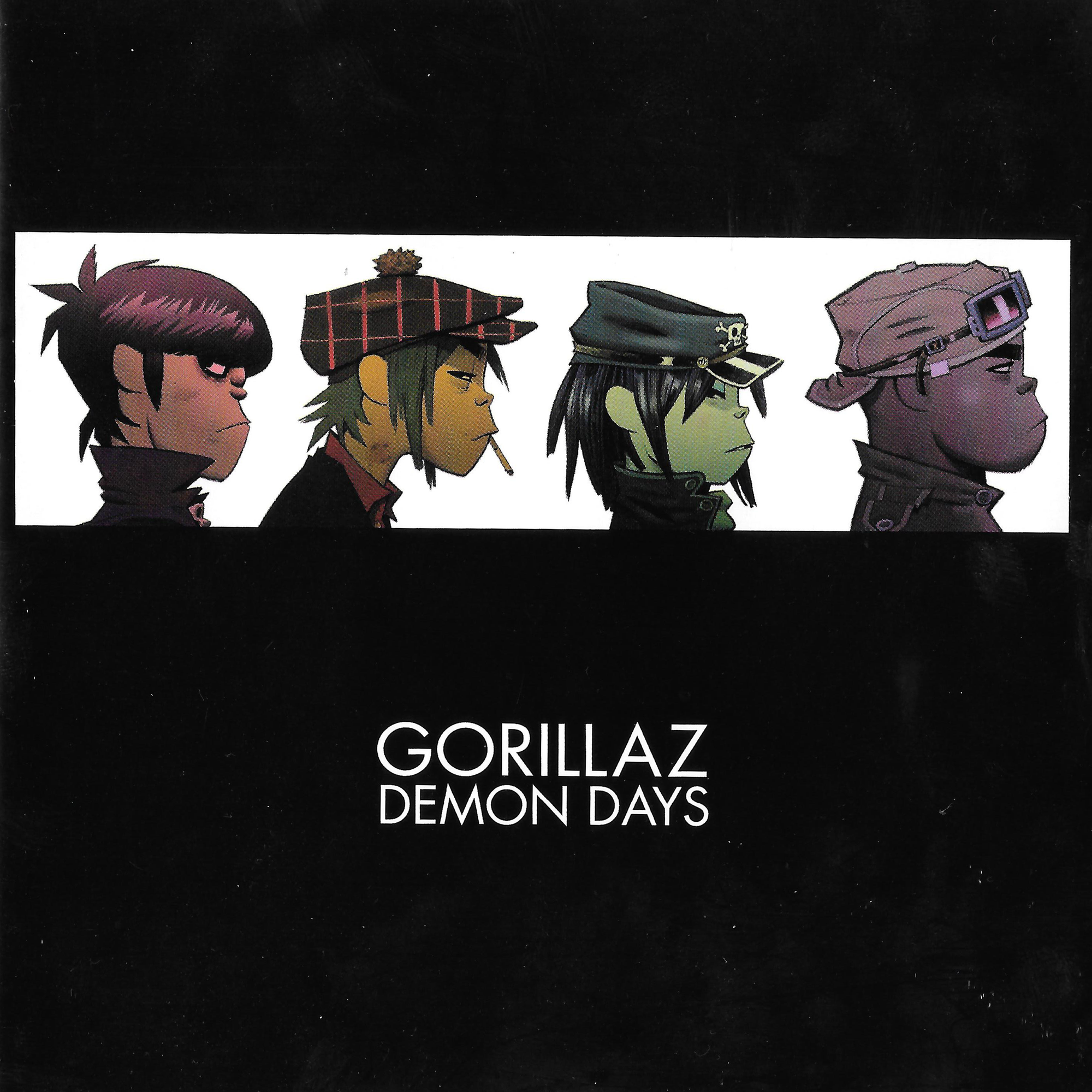

In the beginning, nobody seemed to take Gorillaz seriously. When their self titled debut album was released in 2001, most critics treated the project like a curiosity, a quirky side project for Damon Albarn, then better known as the frontman for the Britpop band Blur. The band’s unique conceit–a virtual band of animated apes masking an army of collaborators–seemed to torpedo the project’s credibility. Reviews of the album were mostly positive, but lukewarm, peppered with snarky jabs and backhanded compliments. Pitchfork called it a “smarmy promotional gimmick” and a “conceptual failure.” NME wrote that “All this exciting experimentation sure makes for some dull listening.” Rolling Stone described it as “a soundtrack CD to the jaw-dropping animation Web site gorillaz.com,” and the Guardian wrote that “Like any good cartoon, Gorillaz are difficult to love deeply, but impossible not to like.” The general consensus seemed to be that Gorillaz was an ephemeral gimmick with songs that were better than they had any right to be.

But for Damon Albarn and animator Jamie Hewlitt, Gorillaz was more than a gimmick. The duo had things to say: about celebrity culture, about the suffocating confines of genre and cultural borders, and about the state of the world itself.. Demon Days, released in 2005, was the result of these efforts. Buoyed by the irresistible “Feel Good Inc.,” one of the oddest songs to ever crack the Billboard Top 20, the record refined the group’s unique collage of styles and proved that the collaborative project was here to stay. It also reflected the changing musical currents of the 2000s, an era where technology was rapidly changing the way we produce and consume music, and social media was reshaping our relationship with fame and celebrity. Despite being dismissed as a gimmick by some at its release, the album’s eclectic style, meta-commentary on celebrity, and environmentalist themes are more prescient than ever before.

Styles Coming out of a Monkey’s Head

Genre labels that have been applied to Demon Days include hip hop, trip hop, indie, alternative rock, dub, afropop, psychedelia, electronic, art rock, disco, britpop and many more. This ability to incorporate so many styles into their vernacular is the hallmark of the Gorillaz sound, and their eclectic approach reflected seismic shifts in music culture that are still felt today.

In 2025, genre boundaries are more fluid than they have ever been. Major pop stars like Olivia Rodrigo and SZA can release pop punk and alternative rock songs with little controversy. Beyonce went from a house album to a country album and is rumored to be working on a rock album. Pop rock crooner Ed Sheeran scored one of the biggest hits of the 2010s with a Dancehall song. Below the mainstream level, the internet offers a spiraling, kaleidoscopic array of niche styles and unlikely genre combinations to explore. The average listener has a virtually infinite supply of the world’s music in their pocket with them at all times, and it is not unusual for playlists (and Spotify wrapped summaries) to span dozens of genres.

However, this was not always the case. In the pre-internet era, genre boundaries were more stable. People tended to listen to a select few genres, and artists were more likely to stay in their specific lane. The reasons for this are both technological and economic. In the pre-streaming era, if you can believe it, people had to pay for physical copies of media (the horror!). Often, you would have to pay money before even being able to hear an entire record. This made genre dividers very useful–if you like one record from the Soul bucket, chances are you might like other records from that bucket. Also, it made it inherently more risky for artists to change styles, because if a fan paid for a record and it wasn’t what they were expecting, they might feel cheated. While there will always be fans who are disappointed in a stylistic shift by an artist, the intensity has definitely changed. For example, it’s hard to imagine something like the backlash to Bob Dylan going electric happening in 2025.

That’s not to say genre crossovers and stylistic departures never happened before the internet, or that Gorillaz was the first project to do so. Early Gorillaz music was compared to the crossover between punk and reggae music that occurred in the UK in the 1970s, a trend that heavily influenced the Clash’s seminal London Calling and which was immortalized in Bob Marley’s 1977 song “Punky Reggae Party.” Artists like the Beastie Boys, Aerosmith, Run DMC, and Beck also dabbled in combining elements of rock and hip hop.

Still, these kinds of crossovers were the exception, not the norm. Artists who did not fit neatly into a genre category were seen as harder to market by record companies. Often, artists needed to be firmly established before they had earned the freedom to experiment. For example, the Beatles experimental psychedelic era didn’t start until they were successful enough to stop touring altogether. And this dynamic was especially prevalent in earlier eras of American pop music, when genre labels were correlated with cultural and racial lines in a divided, segregated country. For Albarn, breaking down cultural barriers was an explicit goal of the Gorillaz project. “More and more, cultural groups are cross-pollinating,” Damon told Wired in 2004, “and we're getting much more interesting art as a result.”

Kids With Phones

The breakdown of firm genre borders accelerated in the digital age. The internet brought the entire history of music to the average listener’s fingertips, rendering record collecting music aficionados obsolete (a dynamic famously explored in another song from this era, LCD Soundsystem’s “Losing My Edge.”) Equally important were advances in recording and music production technology, especially the entrance of the Digital Audio Workstations or DAWs, software platforms that allowed for unprecedented ease and flexibility when creating electronic music. Before DAWs, electronic music would be composed of various bits of hardware like synthesizers, drum machines, samplers and turntables, all of which had to be coordinated in a traditional studio environment. Suddenly, all of this functionality was boiled down into a single piece of software like Logic or Cubase, which could handle the entire process from end to end, dramatically simplifying workflows and opening up new avenues for creation.

The effects of this revolution first materialized in the early 1990s and entered the mainstream in the 2000s. Richard D. James, better known as Aphex Twin, composed singular and arresting music that pushed this nascent technology to its limits throughout the 90's. Radiohead turned heads with their 2000 album Kid A, which used digital production techniques to fuse their signature gloomy psychedelic alt rock with electronic textures inspired by Aphex Twin and similar experimental electronic artists. The mid-2000s saw the rise of Mash-ups, a style of remix that smashed unlikely combinations of songs and styles together to surprising and entertaining effect.

This is the milieu from which Demon Days emerged, and it helps explain the unique feel of the album. In previous eras, artists sought to synthesize disparate styles into a smooth, cohesive aesthetic. Demon Days, in contrast, delights in left turns and jarring contrasts. “Feel Good Inc.” oscillates between De La Soul’s energetic rapping and Damon Albarn’s dejected, lonesome indie rock. “Dirty Harry” starts with a children's choir and bright, chirpy, low fi synthesizers before ominous, cinematic strings introduce an agitated verse from west coast rapper and Pharcyde member Bootie Brown. And in the album’s final leg, “Fire Coming out of a Monkey’s Head,” “Don’t Get Lost In Heaven,” and the title track progress through spoken word, Beach-Boys style 60s vocal pop, reggae and gospel as they tie together the album's key emotional themes.

With this emphasis on jagged, freewheeling combinations of styles, it’s no surprise that Damon Albarn tapped one the most famous (or infamous) mash-up artists of the era to collaborate on the album, the producer Brian Burton, aka Danger Mouse, whose 2004 release The Grey Album sent shockwaves through the music industry.

O Grey World

The Grey Album started with a simple but clever idea–it would be a mashup album combining vocals for Jay Z’s Black Album and instrumentals derived from the Beatles’ White Album. Jay Z had actually released acapellas from The Black Album with the specific intention of allowing people to create their own remixes. While the Beatles tracks had to be extensively chopped, looped, disassembled and reassembled into hip hop-worthy beats. In 2025, this concept sounds like a curiosity, banal even, like something my YouTube algorithm would sandwich between a shoegaze cover of Britney Spears’ Toxic and a recreation of Radiohead’s In Rainbows using only the Mario 64 soundfont. (Yes, I have a very specific YouTube algorithm.) However, in 2004, it was essentially music industry heresy. Originally intended as a limited release for a small audience, the album’s unexpected popularity put it on the radar of EMI, the Beatles’ copyright holder, who promptly took legal action. Despite receiving praise from Jay Z and both surviving Beatles, the album was effectively banned from all legal distribution methods. The legal action even sparked a coordinated protest called Grey Tuesday, where participating websites offered free downloads of the album over a 24-hour period. Protestors argued that since sampling was an art form with the power to radically transform the original material, it should be allowed under fair use doctrine, similar to covers and parodies.

The Grey Album and its resulting controversy brought Danger Mouse into the limelight and advanced his career. He would eventually score a major hit as part of the duo Gnarls Barkely with singer CeeLo Green, and would remain an in-demand producer throughout the 2010s and into the 2020s. Still, if Danger Mouse arguably won the cultural battle, then EMI definitively won the legal war. Sampling law remains virtually unchanged since the 2000s, and The Grey Album, a critical artifact of pop music history, is unavailable on any major platforms or streaming services.

A big fan of The Grey Album was Damon Albarn himself, who was so impressed that he called up Danger Mouse to produce Demon Days. There was just one problem–Albarn’s record label was EMI, the very same label currently threatening legal action against Burton. Needless to say, the label was not pleased. “They said: ‘You can’t work with him,’ and he said: ‘You can fuck right off.’” recalls Burton in a 2015 profile by the Guardian. In the same profile, Buron even claims that Albarn convinced the label to drop their suit against him. Thus, it was Damon Albarn who ultimately secured Danger Mouse’s transition from upstart independent producer to in-demand hitmaker, while simultaneously saving him from potentially ruinous litigation. The opportunity was truly life-changing for Burton, who told Vulture “It was the first time I ever produced an album that was not my own in my bedroom.”

Albarn and Burton would become fast friends and eager collaborators. “We even have that finish-each-other’s-sentences thing happening.” said Burton of Albarn in a 2005 interview with LA Weekly. Both shared an eclectic taste in music and an instinct to break down cultural barriers. For Burton, these instincts came from an isolating upbringing, first as the only black kid in a small town in New York State and then later in a predominantly black school in Stone Mountain Georgia which he described as “a dangerous school, really messed up.” It was here that he first got into hip hop, while a chance encounter with Pink Floyd in college caused him to question the unspoken racial divide in popular music and helped inspire The Grey Album. “I always felt it was so silly – hip-hop kids in one corner, rock kids in the other. I wanted people in both corners to see the other side.” Burton told the Guardian.

While Albarn and Burton’s collaboration forms the backbone of the album, so much of Demon Day’s vibrancy comes from its rich cast of collaborators and guest stars. A recurring device on the album is an interplay between Damon’s depressive vocals and guest verses from oddball rappers. Albarn, who claims to have refused to work with Eminem on the album, favored more idiosyncratic voices from the world of hip hop. Notable rappers that appear on the album include NYC underground hip hop legend MF Doom, who drops characteristically absurdist and hilarious verses on the lumbering, crusty experimental boom bap of “November Has Come.” De La Soul and Bootie Brown of the Pharcyde both deliver energetic performances that dramatically shift the vibe of singles Feel Good Inc. and Dirty Harry, respectively. Rapper Roots Manuva, meanwhile, lends his distinctly British voice and lyrics to the trip-hop inflected psychedelic electronic of All Alone.

Of course, the Demon Days collaborators were not limited to the world of hip hop. It seems fitting that vocalist Shaun Ryder appears on the irresistible single DARE, since his band Happy Mondays was blending elements of hip hop and psychedelica back in the late 80s in the hard-partying “Madchester” scene (famously depicted in the film 24 Hour Party People.) Ike Turner, husband and musical partner of Tina Turner, plays piano on the slinky, oddly blues-y Every Planet We Reach is Dead. Perhaps most surprisingly, actor Dennis Hopper delivers an extended monologue in the form of a parable about greed and environmentalism on the trippy Fire Coming Out of a Monkey’s Head. This freewheeling, unpredictable blend of voices is perhaps the greatest hallmark of the Gorillaz sound, and a constant source of energy and excitement on Demon Days.

Feel Bad Inc.

A 2005 New York Times profile of Damon Albarn, fresh off of the release of Demon Days, opens like this:

“On the wall of his recording studio, Damon Albarn has written “Uncertainty Leaves Room for Hope” in large black letters. Nearby, the phrase “Dark Is Good” has one “O” crossed out, making it “Dark Is God.”

While Demon Days finds joy in its collaborative spirit, it also contains a healthy dose of darkness. While the record’s absurdist lyrics and oddball asides don’t necessarily amount to a concept album in the strictest sense, the album nevertheless explores consistent themes of societal decay, environmental degradation, and dehumanization. “All the songs are like episodes of my worst fears,” Albarn told Times in 2005. “Maybe, hopefully, I’ve got them out and they’re not going to come true.”

This darkness is partially baked into the Gorillaz project itself. The cartoon band “gimmick” that critics scoffed at was, in and of itself, a self-aware commentary on fame and celebrity. In the above NYT interview, Albarn describes his disillusionment with fame, his sense that the media had misrepresented his band Blur’s commentary on British culture and overly fixated on his high-profile feud with fellow britpoppers Oasis. “You get sick of your own voice, you get sick of seeing yourself on covers of magazines.” Albarn told the times. “You turn into, well, a cartoon.”

Born from a chance situation, wherein Albarn ended up moving in with Tank Girl illustrator Jamie Hewlitt out of convenience, Gorillaz would provide Albarn with a new vehicle to keep “making music and art that are pure products of our influences while not really having to let the whole celebrity side of it get in the way,” as Albarn put it in a 2005 interview with Wired. It also served as a commentary on the artificiality of celebrity, especially in an era when social meda was increasingly defining how fans engaged with stars. After all, if celebrities and superstars can create heavily curated realities and increasingly bake personal lore into their public image and work, why not go one step further and create an altogether fictional band, with its own absurd and entirely fictional lore? Gorillaz arguably were not doing anything all that different from how stars behave today, they were just more up front about it. As Jamie Hewlett put it in a 2005 interview with Wired: “If you're going to pretend to be somebody you're not - which is the whole point of being a rock star - then why not just invent fake characters and have them do it all for you?”

It’s hard not to see early Gorillaz moments, like their eerie performance with Madonna at the 2006 Grammy Awards, as precursors to some of the more absurd moments from popular culture of the past twenty years, except in the case of Gorillaz, the existential dread was intentional.

This fixation on celebrity is also present in early concepts for a Gorillaz movie that was originally intended to form the basis of their second album, which was ultimately scrapped. The film would take place in an apocalyptic future where celebrities' over-inflated egos would be personified as boils and turn them into zombies. It is also conveyed in the slogan Reject False Icons, an early working title for Demon Days that was also the basis of a viral marketing campaign.

Beyond just celebrity and fame, Demon Days conveys a sense of societal dread and the fear of a less kind, less flourishing future. One moment of inspiration for Albarn came from a train trip he took in northern China through a 200 mile stretch of land that had been devastated by farming. His environmental concerns manifest on songs like “Last Living Souls,” “O Green World,” “Every Planet We Reach Is Dead,” and the final three tracks of the album. Other social concerns included the 2003 Iraq War and the September 11 attacks in 2001, both of which contributed to Damon’s fear of the coming demon days. It’s also hard not to feel the impact of the 1999 Columbine massacre on the song “Kids With Guns,” in which Damon croons “They’re turning us into monsters.” For Albarn, the titular “Demon Days” represented his fear that humanity was entering an era where greed, technology and mass media would bring about a world of fear, loneliness and environmental collapse. Luckily nothing like that is happening now and everything is going great. :)

Every Planet We Reach Is Gorillaz

Demon Days, like its predecessor, was met with middling reviews; critics really had a hard time with the whole “virtual band” thing. But the commercial success of the album and its singles proved that the project was here to stay. By the release of their third album Plastic Beach in 2010, the Gorillaz project had eclipsed Blur in terms of popularity. It had also become a sort of boundary-smashing meeting point for iconic voices from all different strains of music. Plastic Beach is, to my knowledge, the only album that boasts cameos from both Snoop Dogg and Lou Reed. It also includes contributions from Bobby Womack, Mos Def, De La Soul, Yukimi Nagano of the group Little Dragon, Mark E. Smith of The Fall, the Syrian National Orchestra for Arabic Music and, just for good measure, 50% of the Clash. If Damon and Hewlett had something to prove when they started Gorillaz, with Demon Days they had inarguably made their point.

Today, the album is widely regarded as a modern masterpiece. Its adventurous sound and sociopolitical themes remain prescient 20 years later. It also represents a historical artifact that heralds musical, cultural, and sociopolitical shifts that accompanied the new millennium, trends that are still with us today. We are, for better or worse, still living in the world of Demon Days.